#6: On Soul

The double bind of civic engagement, restorative justice, and a whole bunch of other hectic stuff.

‘Wins of this magnitude can never be a celebration of/for one person, but instead are a celebration of collective effort, a constellation of known and unknown miracles. The same way the troubles that we’ve been visited with cannot be assigned to one person. A person can serve as a symbol, a symptom, of what is unresolved in the whole, a manifestation of collective terrors and an effort, however immoral or depraved, to possess certainty.’ — Prentis Hemphill

An open question:

Is active civic participation the sign of a healthy democracy, or is it the marker of a failed state which desperately hinges on concerned citizens trying to bail it out — bucket by bucket, even as more water seeps in through foundational cracks that we stubbornly refuse to plug? My guess is both, but man, it’s difficult to tell the difference sometimes in America.

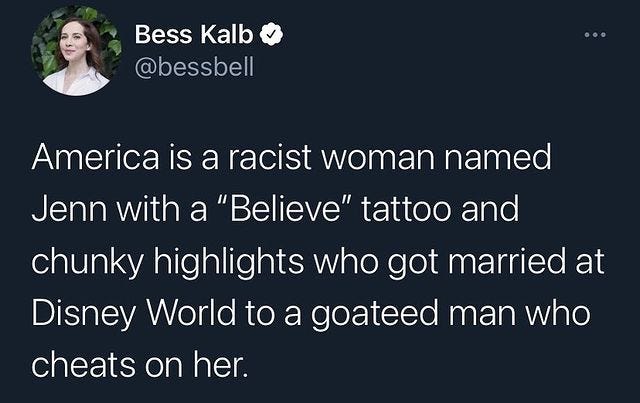

I am rarely surprised by — but always deeply depressed by — the sight of the United States’ latent racism laid plain. In fact: sue me for sounding jaded but I’m confounded by the volume of fellow white people expressing surprise that this election could still be as tight as it was, people asking: Have we, the American people, learnt nothing over the past four years? I mean… when do we ever learn? What precedent in American history, sentiments, and systems would lead us to reasonably expect as much — or to expect that anything could have changed substantively in our fundamentally violent settler colonial state as long as white supremacy runs rampant, aided and abetted by institutions of the state? Look, even Nate Silver was sensible enough to not predict a landslide.

Slam poet Guante writes, ‘White supremacy is not the shark. It’s the water’. Removing Donald Trump from office is just one part of the solution, he writes; step one ‘is affirming that these problems are fundamentally bigger than individual attitudes or actions… Our work is not just the work of changing people’s hearts and minds; it’s the work of changing our institutions, laws, policies, media, and systems too.’ Mirroring this sentiment in TIME Magazine, Brittany Packnett Cunningham writes: ‘Trump was always the symptom. He was never the virus.’

Perhaps this is why I’ve taken issue, over many months, with the Biden campaign’s propensity for language centred around the ‘soul’ of the nation: restoring it, fighting for it, etc. This has been the rhetorical battle of the election, with both sides positing that they are the true champions for America’s soul. Ironically, this language almost made more sense coming from Donald Trump, in that the Trump era has rendered evident the chilling depths at the vacant heart of the nation. (The sickening takeaway of this election is the realisation that 70+ million voters looked into the soulless void of the Trump regime and said, ‘yes, sign me up for more of this’.) From the Biden camp, however, I find this obsession with the soul of America irksome. At best it is superficial, in the jingoistic way that American campaign rhetoric often is. At worst it evinces a willfully simplistic misrepresentation of Trumpism’s structural genesis.

Keeanga Yamahtta-Taylor writes in the New Yorker:

‘Like tens of millions of Americans, I voted to end the miserable reign of Donald J. Trump, but we cannot perpetuate the election-year fiction that the deep and bewildering problems facing millions of people in this country will simply end with the Trump Administration. They are embedded in “the system,” in systemic racism, and the other social inequities that are the focus of continued activism and budding social movements. Viewing the solution to these problems as simply electing Joe Biden and Kamala Harris both underestimates the depth of the problems and trivializes the remedies necessary to undo the damage. That view may also confuse popular support for fundamental change, as evidenced by Trump’s one-term Presidency, with what the Democratic Party is willing or even able to deliver.’

President-Elect Biden’s Saturday victory speech was written by presidential historian and biographer Jon Meacham, in whose 2018 book (The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels) this Biblical language is rife. In the speech, Biden celebrates the opportunity ‘to rebuild the soul of America, to rebuild the backbone of this nation, the middle class and to make America respected around the world again.’ There is much in these words that generates hope and prosperity. (On the most basic level, it’s a relief just to hear complete sentences and to know that there is finally an adult in the room, not a bunch of fascist muppets). And when Biden uses words like ‘rebuild,’ I know he is largely referring to tangibly positive — even essential — actions such as the green jobs plan or the pandemic response.

But I also chafe at the underlying rhetorical implications at play here. On surface, ‘making America respected around the world again’ is something that is desperately necessary. On a more implicit level, though, what does this language say about where the baseline of ‘normalcy’ is set — and about a failure to look beyond that? (Thinking here of Edward Said’s critique of ‘imaginative geographies’ in the imperialist worldview.) It bears acknowledgment that much of the globe has only ever respected America in the grudging way one respects the blunt and omnipresent force of a playground bully — and that they should never have been obligated to respect it, or be impacted by it, at all. Biden’s words are predicated on the assumption that America previously was universally admired, and that at present it is not, and that we must aspire to return to the prior state. This lacks nuance. From view of much of the world, the past four years have been less a fall from grace and more a (frightening) recognition of an underbelly which has always existed at America’s core.

In committing to being a one-term president, a transitional figure, Biden is signalling a desire to get things back on track. We therefore need to be careful about what that track is. Clearly the good old days weren’t quite so good, if they led us into this mess. (As per playwright Lorraine Hansberry: ‘Comfort has come to be its own corruption.’)

Before last week’s post-election celebrations, the only time I can remember gathering in a crowd in downtown Washington out of joy rather than in protest was Obama’s first inauguration. January 2009 was bitter cold. Watching my breath rise in the frigid air, I was proud to be there, witnessing what was unfolding. At 13, it was also the first election cycle I had avidly followed and held my own opinions on. Packed elbow to elbow in winter coats, gazing up at Jumbotron screens on the National Mall, it felt like a dawn of a new liberal, post-racial dream that there could be no going back from. Sarah Palin and her absurd TV-worthy antics seemed definitively in the rearview mirror. But just eight years later, Donald Trump became our racist, reality-TV president. When we look back at history, we piece together narrative threads, patterns. Whether we see them in real time or not is up to our collective and individual blindness.

The Washington Post’s Monica Hesse puts things well (emphasis is mine):

‘Anecdote isn’t evidence, but I’ll note that for the past two years, the demographics in my inbox who most fervently believed in a 2020 blue landslide were white liberal men and occasionally white liberal women. Surely, they insisted, what had happened in 2016 was a blip […] The Black women who wrote to me, meanwhile, were exhausted and often worried. To them, 2016 didn’t feel like a blip. It felt like the America they’d already been living in for decades was finally made visible to the rest of the country. […] The bad parts of America are not blips, they’re characteristics […] Do you know how hard it is to love this place sometimes?’

This election’s record voter turnout is potentially more of an indictment of the desperate state of the nation than a glowing example of Americans’ inherent passion for civic engagement. (Importantly, it is also a testimonial to the phenomenal organising efforts of individuals and groups like Stacey Abrams’ Fair Fight foundation, Mijente’s #FueraTrump campaign, the dad-joke Obama bros at Vote Save America, and the Navajo Nation and other Indigenous peoples in Arizona.) Civic participation is always a net positive, and the opportunity to participate is a right that necessitates considerable protection — I would never argue otherwise (nor would the sixteen hours I spent on Election Day handing out hundreds of paper ballots to eager voters, many of them first-timers).

My point is more to acknowledge how flawed a system is if it necessitates vast swaths of citizens to expend so much energy fighting for their rights, and lives, that it feels impossible to get above that baseline to build something new, imaginative, better. Participation then becomes crucial, and often difficult. It is like treading water against a current — yet is rarely fulfilling. It’s a double bind: a zero-sum game, only with no sum. The fact that this contest was a nail-biter rather than a landslide is a tremendous condemnation of not just the American people’s values but more broadly of the institutional pillars and organising principles of the American democratic experiment itself. This house does not have good bones. Yet here many of us are: continuing to bail water out from the basement even as we insist on keeping the windows open, complicit in flooding more water in.

What is at the soul of a nation that systemically puts so many of its people in this untenable situation? How much, I sometimes wonder, can we ever expect from a nation built like this?

How do we coexist?

So, we have to somehow continue to share space with these people (you know. The ones in the hats). This is an inflection point for America, a potential window for reconstruction. The stratified identity politics which the Trump era has thrust into plain sight will not disappear neatly; as Helen Lewis writes in the Atlantic, ‘a force as powerful as Trumpism doesn’t just vanish—and neither does the political logic underlying anti-Trumpism, even if the constituent elements drift apart.’ Using the residual ‘hangover’ of Britain after Brexit as an example, she writes: ‘When a political affiliation merges with an identity, it becomes deeply emotional. The knot is hard to untangle.’

How is it even possible — let alone desirable — to try to find shared humanity with individuals who hold abhorrent beliefs, or to try to build bridges and disprove them of their notions? On one hand, how else to permanently defuse their power (I for one am already stressed that the Trumpist contingent will find a new, more sophisticated figurehead, like Sen. Tom Cotton, in 2024). But on the other hand, what kind of fucked up concessions to their narratives and false equivalencies are we making by doing so?

This last bit is particularly pertinent re media coverage and attention. We all know that Trump voters aren’t out here en masse trying their best to empathise with the psyche of the Biden voter. That’s something that blue America — or at least the media — can’t even manage to do sensibly:

From my research on transition-era restorative justice mechanisms in other countries, I’ve learnt it’s not uncommon for modalities of restorative justice to unwittingly sacrifice nuance — the preservation of dignity, the potential for compounded trauma — in the name of broad, sweeping ‘reconciliation’. The people who stand to benefit the most from paradigms of amnesty, at least in quantifiable ways, are the aggressors.

Packnett Cunningham writes:

‘The voices of those who won this election in the trenches of Black and brown communities have been drowned too often by white voices who insist the reconciliation requires pardoning the harm done. But those of us who handed the Democrats a win, all while resisting the worst of white supremacy with few resources and vacillating support, have one resounding thing to say: not so fast. America must not simultaneously thank Black and marginalized communities for an arduous victory and shun our demands for an end to our continued systemic oppression. Gratitude must reap material reward.’

In any case: restorative justice hinges on truth, presented in such a way that there is a shared awareness of it. Truth is what then leads to reconciliation. How can this truth to reconciliation pipeline operate in an environment currently saturated with accusations of #fakenews? How to balance a longterm vision for collective unity with a zero-tolerance policy for hatred, untruth, or conspiracy? And then how do white people, like myself, juggle the responsibility to come collect our people with the inescapable fact that the time is long since past to extend understanding to the worst of them? (I realise this is a loaded set of questions to ask, but I feel they’re worth voicing — please don’t @ me for this.)

Furthermore, how to acknowledge these difficulties of the restorative model, without getting bogged down in a carceral framework? (In other words: is it morally permissible that I can’t wait for Trump to go to prison, even though I normally subscribe to the belief that prisons as we know them shouldn’t exist? Someone please tell me the answer is a resounding yes??)

Now what?

Well, first there are the Georgia Senate runoffs. Following that: I’m no political theorist, but I see value in ranked-choice voting. A handful of states, and New York City, have already experimented with this. It’s a way to begin to erode the two-party dichotomy without the harmful side effects of vote-splitting, and to encourage candidates and parties to campaign on the basis of what they have to offer rather than simply against their opponents.

In the longer term, I strongly believe in the abolition of the electoral college. (Although — to return to the subject of language — I do feel that the ‘abolish the electoral college’ sentiment gets thrown around a fair amount in leftist circles as shorthand to telegraph shared priorities/values, sometimes without full recognition of how much of a structural challenge it actually will be to accomplish this.)

But what about beyond these specific line items? What to do about the matter of the soul of the nation?

‘The rot is deep. This is not unpatriotic to say,’ Packnett Cunningham writes. (An echo of Baldwin’s famous words in Notes of a Native Son: ‘I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticise her perpetually.’) And so on an overarching scale, Packnett Cunningham puts forth the idea of ‘disciplined hope’ — which, she says ‘requires an honest assessment of the problem, an unrelenting belief that it can be changed and an undistracted pursuit of what’s better’.

Yamahtta-Taylor concludes that:

‘The demonstrations of the summer, the ongoing campaigns for mutual aid, and the growing movement against evictions are demonstrable proof that power is not only generated in mainstream politics but can be garnered through collective organising and acts of solidarity. They also foretell a future in which the country does not return to a long-forgotten normal but is animated by protests, strikes, occupations, and the ongoing struggle for food, medicine, care, housing, justice, and democracy.’

This brings us back to my initial question of bailing water from the basement. Perhaps the conversation I ought to be raising is less a referendum on civic action and more a nod to the power of collective organising — something which undergirds civic participation but, crucially, also functions wholly independently of political frameworks.

Assata Shakur said it best: ‘No matter who wins this election, it will take abolition to create our future. No matter who wins this election, it will be up to you to create networks of care that sprawl across normative divisions. No matter who wins this election, it will be your duty to fight, to win, and to love one another.’

No fun bonus links today,

Because this has already been enough of a novel (sorry, but also… sorry?) But as always I recommend clicking the embedded links throughout this, if you have time/interest. They function as footnotes and occasionally Easter eggs.

Catch ya next week (which I promise will be considerably less America-centric),

Maddy