#30: On Documentary

What's an octopus gonna do with a statuette anyway hey?

Hi friends,

I’m coming to embrace the fact that recently this newsletter is mostly just a platform for me to rant and rave about movies (since that’s all I think about these days anyway). So, on that note…

South African independent cinema, though criminally under-resourced, is just… so good. So good, man. For various complicated reasons (funding and distribution woes) and less complicated reasons (ignorance and lack of interest from abroad) the rest of the world rarely sees much of it. Foreign perception of South Africa tends to be self-fulfilling and cyclical, and this manifests in film and media. The scope of this limited perception from abroad kneecaps its potential expansion by way of a predilection toward funding, awarding, and supporting media output which perpetuates such myopia. The frustration that this reality elicits on the home front is something which is difficult to articulate outright, but which seeps out in implicit ways. One such example is the ambivalence many Cape Town documentary folks have had toward My Octopus Teacher’s recent awards sweep.

Look—I, and many others, enjoyed the documentary a fair amount. It’s endearing (if occasionally saccharine). The cinematography is stunning. Watching it made me want to head down to Cape Point, throw on some fins, and dunk myself straight into the chilly False Bay waters for a dive. It is fun to see the striking landscapes we call home have their 15 minutes of global stardom. And, tellingly, it is noteworthy for any South African documentary to reach such heights.

But largely the local consensus has been that it was an entertaining film but not Oscar and BAFTA-worthy—at least, not to those of us who know the innovation, creativity, and diversity of narrative and voice that South African cinema is a) capable of exhibiting and b) which rarely if ever enjoys this degree of funding, recognition and acclaim. It is difficult, for those of us immersed in the South African film world, not to see My Octopus Teacher’s success dually: as both a triumph of local cinema, and simultaneously as an example of that which is otherwise usually denied. This isn’t to say that this film is undeserving, in a vacuum, of acclaim. Rather that (since the world is not, in fact, a vacuum) My Octopus Teacher’s global success stands in stark contrast to the lack of support—both pre and post-production—that African and South African cinema receive most of the time. Would this particular story have been snapped up as a Netflix Original if Craig Foster weren’t already a well-known and very well-connected filmmaker and conservationist (who fortunately happens to also make for a reasonably engaging and inoffensive protagonist)? Would viewers take to the film as eagerly if it dealt with human issues, not sweetly anthropomorphised animals and a backdrop of nature porn? This latter question sounds facile—of course people contain multitudes and can care about multiple issues—but I stand by it. One can’t help but notice the elements of privilege that set this film apart from other South African documentaries, and wonder if these are the reasons for the film’s smash success.

Two of my lecturers in UCT’s Centre for Film and Media Studies, Liani Maasdorp and Ian Rijsdijk, wrote a salient op-ed recently about exactly this. Winning Best Documentary at the Oscars amid a nomination field of heavy social-impact hitters—such as the Obama-produced Crip Camp and Garrett Bradley’s abolitionist tour de force Time—it is clear that My Octopus Teacher is the latest in a tradition of South African films getting recognition on the global stage when they are situated as ‘the feel-good choice’. A critical viewer, Maasdorp and Rijsdijk write, might object to My Octopus Teacher following in the ‘well-trodden path of privileged white males documenting and representing the exotic other… But as it shot up the rankings on Netflix, it became clear that these flaws were not an obstacle to millions of viewers around the world who embraced the film wholeheartedly. Indeed, while the film’s unabashed sentimentalism and Foster’s somewhat self-indulgent narration invited both parody and critique, even the surliest of critics was carried away on a tide of “the feels.’

‘There are scant few financing and distribution networks for African cinema,’ Tambay Obenson notes in an IndieWire piece from late 2019. ‘Creating documentaries on the African continent remains a challenge for the same reasons that face narrative filmmaking in the region: a lack of a sustained ecosystem. But with challenges come opportunities — in this case, the chance to build a documentary tradition and legacy for future filmmakers.’ And things are changing, that’s for sure. Production funds and programmes created by and for African filmmakers have sprung up in recent years in SA and across the continent; Nairobi-based Docubox comes to mind, for one, as well as anything that the ubiquitous Steven Markovitz touches. And, reaching out from across the ocean, Doc Society, the IDFA Bertha Fund, etc, offer grants and funding/screening opportunities as well. But all of these entities primarily funnel into the indie festival circuit. To funnel from there into the Academy Awards, for instance, is a further hurdle which requires attention from (who else) the US media—one of the criteria for an Oscar nomination being a review from one of a handful of New York and Los Angeles newspapers. The nitty-gritty of all this sends us down a rabbit hole that I’m not particularly knowledgeable in so I’ll cap it here. My point in raising all of this is to highlight the fact that both these issues and their solutions are twofold: involving international viewers and critics being willing to engage in stories from the continent as well as funders, award circuits, and distributors being willing to do so too. The latter facilitates the former. It’s important, even as we cheer for the success of one SAfrican film making it big globally, that we zoom out to see the full context of why it occurred for this specific film and why it generally occurs so rarely.

As for My Octopus Teacher’s impact, other than being a blessing for Western Cape tourism (Half joking here… but surely there must be CCTV footage of Tim Harris sitting in Wesgro HQ on Oscar night, cackling maniacally…) Hopefully its success will boost the South African documentary industry’s profile in the eyes of the international film world. But as Maasdorp and Rijsdijk explain, there is a crucial caveat: ‘We think it could lead to wonderfully positive outcomes. But only if marginalised South Africans have agency and power in front of and behind the cameras.’

Speaking of South African cinema,

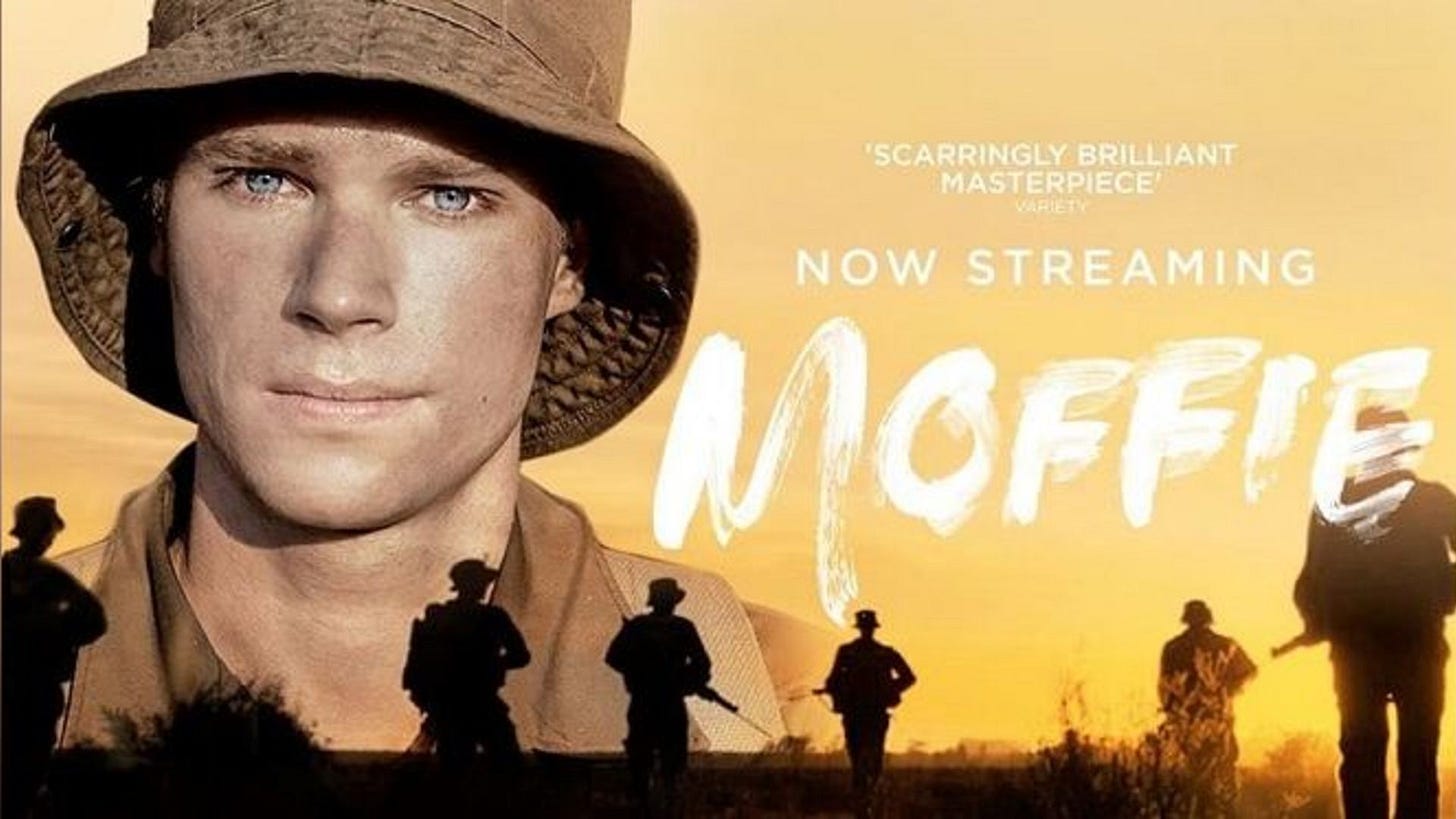

Here’s a beautifully-written essay by Mark Gevisser in the New York Review of Books on Oliver Hermanus’s 2019 film Moffie, which has finally been released in the US. I say ‘essay’ because calling it a review doesn’t do it justice. Gevisser is one of South Africa’s preeminent writers on gender and sexuality, and came of age at the time that the film takes place. He articulates everything that is special about this thoughtfully rendered film, which genuinely blew me away when I watched it last year. Highly recommend the film (and the review) if you haven’t yet seen it.

A few other quick links:

George W. Bush Can’t Paint His Way Out of Hell: The Chilling Spectacle of Watching the Political Class Redeem a Criminal, Again: by Sarah Jones for NY Mag.

Poet/classicist Anne Carson on ‘The Sheer Velocity and Ephemerality of Cy Twombly’. A great, talking about a great—it’s great.

Arundhati Roy, on India’s covid crisis, in the Guardian. A must-read.

To end on a lighter note, an extremely low-stakes deep dive: Why Am I Sp Bad At Typign? by Katie Notopoulos for Buzzfeed News.

That’s all for today! Til next time,

Maddy

P.S: This is Cold Brew issue #30! That feels like a big number, which is kinda wild. Thanks as always to everyone who tunes in and reads this thing. I appreciate you lots.